The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty as the First Distributed Ledger Technology in Korea

Joseon, the last dynasty of Korea, disappeared from the stage of history on August 29, 1910, when it was forcibly annexed by Japan. Nevertheless, today we know the history of the Joseon Dynasty in surprisingly great detail. The key reason is the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty.

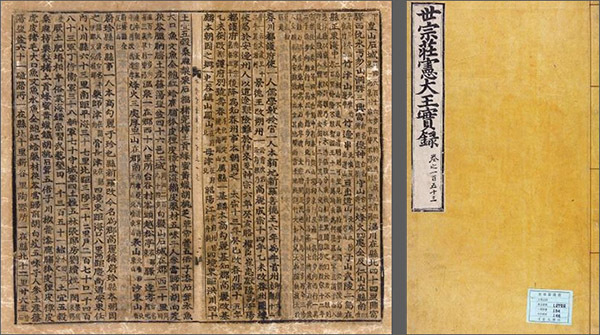

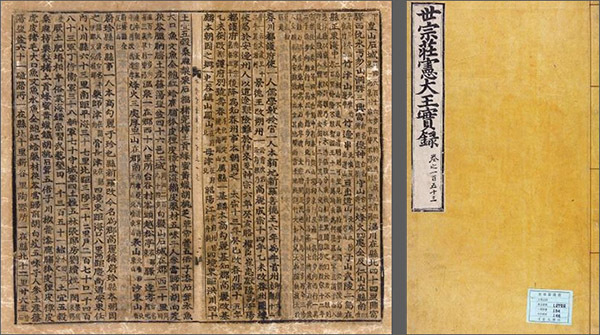

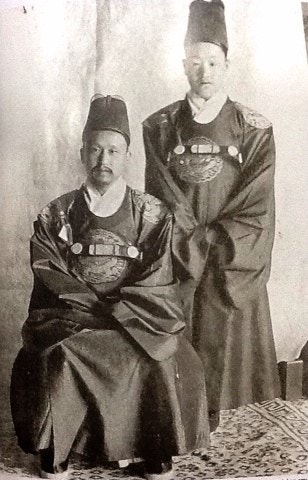

The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty are the official history records of the Joseon Dynasty and a UNESCO Memory of the World. Each volume of these annals was officially compiled after the king’s death. When considering the objectivity of records, the Annals of King Gojong and Annals of King Sunjong, which were written under the “supervision” of the Japanese during the colonial period, are usually excluded from the official records. The last two kings, Gojong and Sunjong, passed away after the annexation, meaning their annals were compiled after Joseon had already vanished. However, since they were modern figures, there are plenty of other records to reference besides the Annals, and even photographs remain.

The Annals possess unique characteristics compared to other global archives. Among them, two features, in particular, can be viewed from the perspective of Distributed Ledger Technologies.

1. A Record Even the King Could Not Edit

The first feature that makes this history book special is that it was taboo for even the king to read as well as to edit the Annals. This was to ensure the objectivity of the records. Historians regarded this as a calling and sometimes risked their lives to leave records. A representative anecdote showing this objectivity is the record from February 8, the 4th year of King Taejong (1404). One court historian recorded the very words the King said to “not record.”

The King personally rode a horse with a bow and arrow to shoot a roe deer, but the horse fell, causing him to fall off, though he was not hurt. Looking left and right, he said, “Do not let the court historian know.”

Source: Annals of the Joseon Dynasty

At this level, it seems fair to call the Annals an indeed write-only log.

Of course, there are no absolutes. Some kings tried to read or modify them. Even in exceptional cases, the king did not view them directly but went through a procedure where officials checked specific parts. This actually happened during the reign of Yeonsangun, the 10th king; after seeing the records, the king was enraged, leading to a bloody purge.

Modifications were not entirely non-existent. However, it was not a matter of deleting and overwriting existing content, but rather appending revised versions. In other words, it was an append-only method. To compare it to blockchain, it is akin to a hard fork-creating a new chain from a certain point rather than changing the existing block. Joseon was thorough, almost to the point of obsession, when it came to record-keeping.

2. The Ledger Replicated in Four Locations

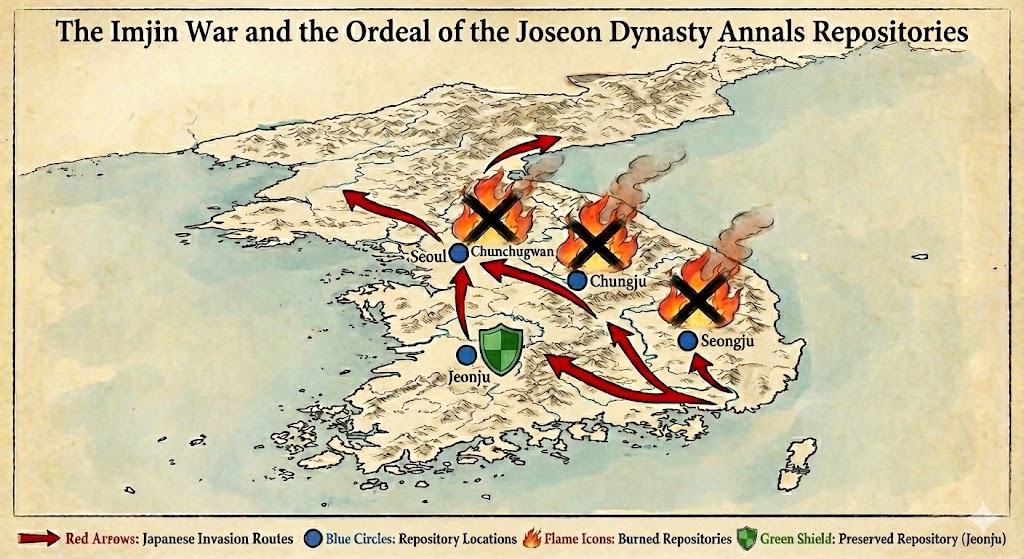

The second specialty is distributed storage. From the time of King Sejong the Great, the 4th king and the creator of Hangeul, the Annals were printed and stored in three additional locations (Jeonju, Seongju, Chungju) besides Seoul. Because of this characteristic, I believe it is not an exaggeration to call the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty Korea’s first Distributed Ledger system.

Thanks to this distributed storage structure, the Annals were fully preserved despite two devastating wars. During the Imjin War (Japanese invasions wiped out nearly 20% of the population) in 1592, the Japanese military took only 20 days to advance from Busan to Seoul. Three out of the four archives (Seongju, Chungju, Seoul) were located on the invasion route, and they burned down almost simultaneously. What might have seemed excessive—”storage in four locations”—ended up being just enough to save one copy during the actual war. If the legendary, undefeated Admiral Yi Sun-sin had not defended Jeolla (the southwestern province), it is highly likely that even the last copy in Jeonju would have disappeared.

After losing most of the archives during the Imjin War, Joseon performed a “system update.” This time, they moved the archives not to vulnerable major cities, but to an island (Ganghwado) and three deep mountains. The number of storage sites (4 → 5) and the decentralization of terrain (City → City, Island, Mountain) were upgraded. During the massive attacks by the Qing Dynasty in 1627, the archives in the capital and the island were burned, but the mountain archives were out of reach, preserving the Annals intact.

Korea had various other history books, including the History of Goryeo, and many historical texts around the world existed and vanished. However, the reason the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty exist today is not simply because they are relatively recent, but because they took the form of a distributed ledger system with strong resiliency.

Considering the objectivity of the records, the Annals are impressive for their content alone. But the fact that they designed such a system and operated it for hundreds of years is even more surprising. It is truly a proud legacy of Korea.

한국의 마지막 왕조인 조선은 1910년 8월 29일에 일본에 강제 병합되면서 역사의 무대에서 사라졌다. 그럼에도 불구하고 오늘날 우리는 조선왕조의 역사를 놀라울 만큼 자세하게 알 수 있다. 그 핵심 이유가 바로 조선왕조실록이다.

조선왕조실록은 조선 왕조의 공식 사서이자 유네스코 세계기록유산이다. 이 사서의 각 편은 왕이 죽은 뒤에 공식적으로 편찬되었다. 기록의 객관성을 따져 보면, 일제 강점기에 일본인의 “감독” 하에 작성된 『고종실록』과 『순종실록』은 보통 공식 기록에서 제외한다. 마지막 두 왕인 고종과 순종은 한일 병합 이후에 사망했고, 이미 조선이 사라진 뒤에야 실록이 편찬되었다. 다만 두 왕은 근현대의 인물이기 때문에 실록 외에도 우리가 참고할 만한 기록이 충분히 많이 있고, 사진까지 남아 있다.

조선왕조실록은 전 세계의 다른 여러 기록물과 비교해도 독특한 특징을 가진다. 그 가운데 특히 두 가지를 분산 원장 관점에서 볼 수 있다.

1. 왕도 수정할 수 없는 기록

이 사서를 특별하게 만드는 첫 번째 특징은, 왕조차도 실록을 수정하는 것은 물론 열람하는 것조차 금기였다는 점이다. 기록의 객관성을 지키기 위해서다. 사관들은 이를 일종의 사명처럼 여기고 때로는 목숨을 걸고 기록을 남겼다. 기록의 객관성을 잘 보여주는 대표적인 일화가 태종 4년(1404) 2월 8일의 기록이다. 사관은 왕이 “기록하지 말라”고 한 말조차 그대로 적어 넣었다.

친히 활과 화살을 가지고 말을 달려 노루를 쏘다가 말이 거꾸러짐으로 인하여 말에서 떨어졌으나 상하지는 않았다. 좌우를 돌아보며 말하기를, “사관이 알게 하지 말라.” 하였다.

출처: 조선왕조실록

이 정도면 실록은 사실상 write-only 로그라고 불러도 될 것 같다.

물론 ‘절대’라는 것은 없다. 일부 왕은 기록을 열람하거나 수정하려 했다. 예외적인 경우에도 열람은 왕이 직접 보는 방식이 아니라, 신하를 시켜 특정 부분만 골라 확인하는 절차를 거쳤다. 조선의 10대 왕 연산군 때 실제로 이런 일이 있었고, 그 기록을 본 왕이 격분하면서 이후에 피바람이 불었다.

수정도 완전히 없었던 것은 아니다. 다만 기존 내용을 지우고 덮어쓰는 방식이 아니라, 수정본을 추가로 붙이는 형식이었다. 즉 append 방식이고, 블록체인에 비유하면 기존 블록을 바꾸는 것이 아니라 중간부터 새로운 체인을 만드는 하드포크에 가까운 행위다. 조선이 다른 것은 몰라도 기록 하나만큼은 집요하다고 할 정도로 철저했다.

2. 네 군데에 복제된 원장

두 번째 특별함은 분산 저장이다. 조선 4대 국왕이자 한글을 창제한 세종대왕 때부터 실록은 서울 외에 세 곳(전주, 성주, 충주)에 추가로 인쇄해 보관하도록 했다. 이 특성 때문에 조선왕조실록을 한국 최초의 분산(distributed) 원장(ledger) 시스템이라고 불러도 무리가 없다고 생각한다.

이 분산 저장 구조 덕분에 실록은 조선이 겪은 치명적인 두 전쟁 속에서도 완전히 보존될 수 있었다. 특히 1592년 발발한 임진왜란 때 일본군은 부산 상륙에서 서울 함락까지 단 20일밖에 걸리지 않았다. 침략 경로에 네 곳의 보관소 가운데 세 곳(성주, 충주, 서울)이 위치해 있어서, 이 세 곳의 실록은 거의 동시에 불타 버렸다. 평소에는 다소 과해 보일 수 있는 “네 곳 분산 저장”이 실제 전쟁 상황에서는 겨우 한 곳만 남기는 수준이 된 셈이다. 만약, 불패의 명장 이순신 장군이 전라도를 사수하지 못했다면 전주에 보관되었던 마지막 실록마저 사라졌을 가능성이 매우 높다.

임진왜란 이후 대부분 서고의 소실을 겪은 조선은 다시 한 번 시스템 업데이트를 진행한다. 이번에는 방어에 취약한 주요 대도시가 아니라 섬(강화도)과 3개의 깊은 산속으로 서고를 옮긴다. 보관 장소의 수(4곳 → 5곳), 그리고 보관지형의 탈중앙화(도시 → 도시, 섬, 산)도 업그레이드가 되었다. 1627년 병자호란의 청나라의 대규모 공격에 수도의 서고와 섬의 서고는 불탔지만 산속의 서고는 청나라 군이 닿지 않아 조선왕조실록은 온전히 보전되었다. 한국에는 조선왕조실록 외에도 그 이전의 고려사를 비롯해 다양한 사서가 존재했다. 혹은 존재했던 것으로 알려져 있다. 전 세계의 수많은 과거의 역사서가 마찬가지로 존재했었다. 하지만, 조선왕조실록이 지금까지 존재할 수 있었던 이유는 단순히 이 기록이 비교적 최근의 것이라서가 아니라, 강한 복원력을 가진 분산 원장 시스템의 형태를 갖추고 있었기 때문이라고 생각한다.

기록의 객관성까지 함께 고려하면, 조선왕조실록은 내용 자체만으로도 대단한 기록이지만, 이런 시스템을 설계하고 수백 년 동안 운영했다는 점에서 더욱 놀랍다. 그야말로 한국의 자랑스러운 유산이라고 할 수 있다.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: